Welcome to the Mind Campus Online Trauma Resourcing Course

Session 1

Please complete the Course Preparation and follow its guidance before starting this session.

Welcome to your first OTR session. We’re really glad you’re here and using this resource in your trauma recovery. We would like to encourage you to work through all the sessions, even if you find resistance to some of the assignments. Resistance one of the effects of trauma and can defeat us in our recovery.

We suggest that you complete a session each week for six weeks. If you can, set aside a two-hour window on the same day each week to do this work. We know that schedules change and life happens. The important thing is not to rush this process and not to stop either! This is your time, your space and your recovery.

This session will cover:

- What is trauma and why some people get stuck in their trauma recovery

- Learning about cognitive theory

- What role do our emotions play in trauma recovery?

- Introducing your primary trauma

- Overview of the OTR course

- Practice assignment 1

- Review practice assignment and session

This session is theory orientated, you will be learning about PTSD and trauma. As the course progresses the sessions are more practical, you will look deeply at your response to your index (primary) traumatic event.

What is trauma and why do some people get stuck in their trauma recovery?

When an event, or series of events, cause a lot of stress, it is called a traumatic event. Traumatic events are marked by a sense of horror, helplessness, serious injury, or the threat of serious injury or death.

animation top handout 5.1

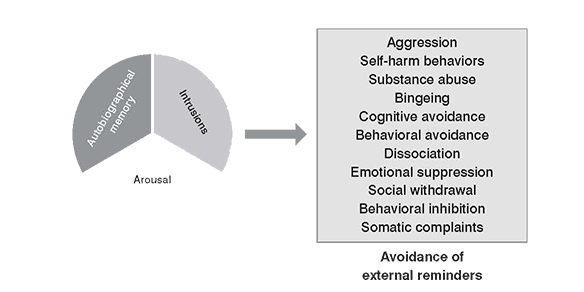

The animation above shows a normal recovery from a traumatic event. Close to the event autobiographical memories, arousal and intrusive memories are closely linked. These effects can be triggered by one another or by external events. This is a natural process that allows us to examine our thoughts and natural emotions. Over time as this process happens the intrusions and arousal decrease, no longer triggering each other. For natural recovery to happen the memories of a traumatic event need to be healthily integrated into our self-view. We best process and form a balanced understanding of an event when we are connected to the thoughts, feelings and memories of what happened.

Some people become stuck in a cycle of experiencing intrusions and arousal. When a traumatic event happens people may experience strong negative emotions. If these intrusive symptoms, emotions, or thoughts are unbearable the person finds subtle but powerful ways to avoid them. There are many ways that people avoid thinking about or feeling their emotions about a traumatic event. Keeping very busy, drinking or using drugs, not coming to therapy sessions, coming late, or not doing practice assignments are all examples of avoidance.

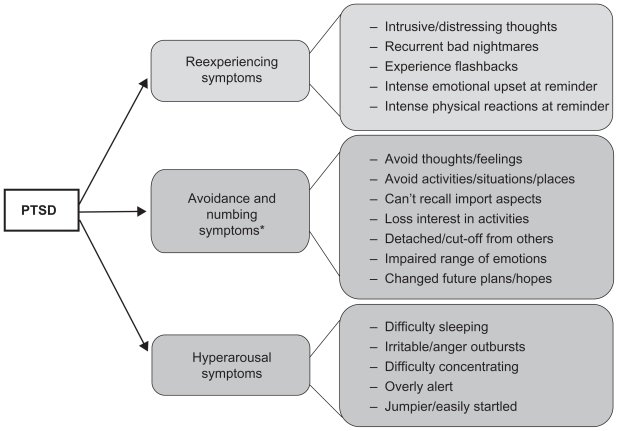

When a severe or repeated traumatic event happens to someone PTSD symptoms are normal for a period of time. Let’s look at some PTSD symptoms and the groups (clusters) in which they occur.

Avoidance stops us from revisiting and integrating memories of traumatic events. Our natural flight or fight feelings (fear, anger, the urge to run) would normally subside soon after a traumatic event, allowing us to move into the process of understanding and integrating memories of the experience into our understanding of the world. In people experiencing PTSD symptoms, the natural recovery process can be stopped by avoidance of emotions, thoughts and expression (talking and writing etc.) of the event. Avoidance behaviours like aggression, substance abuse and social withdrawal can feel like they work, in the short-term. While a person is engaged in avoidant behaviour they may experience a reduction or loss of PTSD symptoms, leading them to continue the behaviour. As the underlying trauma has not been processed, the person may need to rely on avoidance behaviours, to stop PTSD symptoms, to such a great extent that the behaviours in themselves become a serious problem. As you stop using avoidant behaviours you may experience a worsening or return of PTSD symptoms.

TASK 1.1

- Write a list of 5 PTSD symptoms you have experienced in relation to traumatic events.

- Write a short list of avoidance behaviours you have used.

In order to integrate (process) the traumatic event you need to be connected to the emotions and thoughts associated with it, while some form of dialogue (expression) takes place. This process does not need to happen all at once, you can take the steps you are comfortable with one at a time. OTR gives you the tools and structure to move forward in this stage of your recovery.

Learning about cognitive theory

From the time we are born until the time we die; we are bombarded with information. Information comes in through our senses, through our experiences, and through what people teach us. All this information would be completely overwhelming if we didn’t find a way to organize it, and to figure out what to pay attention to and what we can ignore. As human beings, we have a strong desire to predict and control our lives, and we often believe we have more control over other people and events than we really have. Without organizing all the incoming information, we would have difficulty determining what is dangerous or safe, what we like and what we don’t like, or how we want to spend our time and with whom.

As small children, we begin to learn language as a way to organize information. In the beginning, our environment and experiences are very limited, and we have only few words to describe them. A child may call an animal with four legs, a tail, and a nose a ‘dog,’ because that is the only word the child knows—even if the animal is a cat, a pig, a horse, or a lion. As we grow older, we develop more categories that are more fine-tuned, so that we can communicate with others and so that we have a greater sense of control over our world.

The ‘just-world myth’ is taught to children by parents, teachers, religions, or society in general, because as small children we are too young to understand probabilities or more subtle outcomes to behaving or misbehaving. The just-world myth goes something like this: ‘People get what they deserve. If something bad happens to someone, then that person must have committed some wrong previously and is being punished. If something good happens, then the person must have done something courageous or smart or kind before or must have followed the rules. In other words, good things happen to good people, and bad things happen to bad people.’

Parents don’t usually announce to their children that if they behave, they may or may not be rewarded. They don’t say, ‘If you misbehave, you may or may not be punished.’ It is only through the course of time and greater learning that people realize that good things can happen to criminals (for instance, they may get away with crimes), or that bad things can still happen to people who follow the rules and are kind to others. Unfortunately, early learning is not erased, and people often revert to the ‘Why me?’ question when they experience a negative event. They believe that they are being punished for something they did, and if they can figure out what they did wrong, then they can prevent bad things from happening in the future. This is probably one of the reasons why we hear so much self-blame following traumatic events.

The flip side of the ‘Why me?’ question is the ‘Why not me?’ question. This is the source of survivor guilt. We have often heard service members say something like this: ‘It is not fair that my buddy was killed. He was a great guy who was married with two small kids. I’m single and don’t have kids. Why was I spared?’ Or someone may wonder why the tornado spared his or her house but destroyed every other house on the street. The person may feel guilty about being spared when so many other peopleware not. Both questions (‘Why me? Why not me?’) are assuming that all life events are explainable, fair, and potentially controllable.

When a traumatic event occurs, it is a big event, and there are very natural emotionlike being terrified, angry, grief-stricken, or horrified that accompany the event. Your mind also has to find some way to reconcile what happened with your previous beliefs and experiences. If you have never experienced a traumatic event before, your expectation might be that only good things should happen to you. The traumatic event pulls the rug out from under you, and you have to figure out a way to take in this new information that bad things can happen to you. Another thing that people often do into try to change the event so that it matches previous positive beliefs about the world and the sense of control over future events. They may distort their memory of the evenlike saying to themselves that they made a mistake, it was a misunderstanding, or they should have prevented the event. If they can just figure out what they did wrong, they think that they can prevent bad things from happening in the future.

If someone came from an abusive or neglectful home, the event may not be so difficult to accept. That person already has negative beliefs about him- or herself, and this new traumatic event is used as proof of the prior beliefs. The person may think, ‘I am a trauma magnet,’ or ‘Bad things always happen to me.’ In fact, if the person already has PTSD, and negative beliefs stemming from prior traumas, these negative beliefs may be activated after a new trauma event even if they don’t quite fit the new event. An example would be a rape victim who is assaulted by a stranger and says afterward, ‘I don’t trust anyone in my life in any way.’ Why would a stranger’s actions affect one’s beliefs about trust? That belief probably arose from earlier events and is now being reactivated.

One thing that people with PTSD try to do is distract themselves or avoid memories of a traumatic event, as we talked about earlier. But it is pretty difficult to ignore an event so important, and the avoidance is not successful in the long run.

Recovery from traumatic events consists of changing negative beliefs about the self and the world enough to include this new information. It means learning and accepting that traumatic events can happen. A new thought might go something like this: ‘I didn’t do anything wrong. Maybe bad things can happen to good people, and the person who harmed me is the one who is at fault.’ For some people, this thought is frightening, because if it is not their fault, then perhaps all bad things cannot be prevented. If other people blamed you for your traumatic incident, it would also reinforce the idea that you must have done something wrong for the event to occur to you. In fact, if you were abused a lot as a child, you may come to believe an extreme and unhelpful version of the just-world myth: Bad things will always happen because of something about you as a person. Instead of self-blame regarding a single incident, you may experience shame and a deep belief that you are a bad person or deserve only mistreatment.

If you were not alone during the event and had someone else to blame besides the perpetrator and yourself, you might blame someone nearby who didn’t actually cause the event or intend harm. This is another way some people think, to try to get a false sense of control that blaming a perpetrator does not give them. In the military, it is often taught that if all personnel do their jobs correctly, then everyone will come home unhurt. But what if there are an explosion and people are killed, and you cannot see anything you did wrong? In order to keep the idea that your side has control, you might blame someone else in your unit or someone higher up the chain of command. Similarly, a child who is abused by one parent may blame the other parent the most, even if the other parent didn’t know about it.

Another way to cope with a traumatic event is to change your beliefs about yourself and the world to extremes. Here are some examples: ‘I used to trust my judgment and decision-making ability, but now I can’t make decisions,’ ‘I must control everyone around me,’ ‘The world is always dangerous, and you must stay on guard at all times, ’People in authority will hurt you.’ Such extreme negative beliefs may come from flipping from one belief to the exact opposite, or from attending only to negative events and people and deciding that avoiding these is the best way to protect and control your future. Instead of saying, ‘That person hurt me, so I will stay away from that person in the future,’ a trauma victim may blame everyone who falls into a shared class with that person (such as men, women, the military, or people in authority). So, the person may conclude that people cannot be trusted in any way and withdraw from anyone who reminds him or her of the presumed cause of the event. Beliefs can go overboard after trauma in many ways, but common ones are related to the themes of safety, trust, power and control, esteem, or intimacy. These themes may be related to yourself or to others. The more you say something to yourself, the more you may come to believe that it is a fact, and you may stop noticing any evidence that contradicts what you have decided. The problem is that these kinds of beliefs have serious negative effects on your life and continued PTSD symptoms. You have to ignore or distort anything or anybody who doesn’t fit the new beliefs, and you end up isolating yourself from others. We call these thoughts that prevent recovery ‘Stuck Points.’

Stuck points

Click the + to find out more about each point

Black-and-white

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this Desc. of b-a-w thinking

Thoughts, not feelings

desc.

All-or-nothing

desc

Moral statements and 'The Golden Rule'

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

"If-then" statements

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

Not always "I" statements

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

Concise

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

What role do our emotions play in trauma recovery?

Human brains are wired to create emotions in response to dangerous, frightening or even pleasant situations. They help us to quickly understand how to respond, automatic responses are often accompanied by a strong feeling. When the activating event finishes, the danger has passed, these emotions should naturally fade away. We get stuck in our recovery when either these emotions do not have a chance to diminish or we add lots more ‘secondary emotions’ to the trauma.

The feelings generated by our thoughts about an event are called ‘secondary emotions’. An example of this is when a victim, instead of being angry with the perpetrator, blames themself. This usually happens when the thought that if the victim had done something differently the traumatic event wouldn’t have happened is easier than recognising that the event was out of their control and could happen again. This self-blame will often produce feelings of guilt and self-directed anger.

A fire in a fireplace has a lot of heat and energy, like emotions, and you may not want to get too close. If you just sit there and watch the fire and do nothing to it, it eventually burns out. It can’t keep burning forever unless it is given more fuel. That’s what natural emotions from the traumatic event do: They burn out if you just feel them until the energy has burned out of them.

What if you throw ‘thought logs’ on this emotion fire, like ‘It’s all my fault,’ ‘I’m so stupid,’ or ‘I should have known it was going to happen’? You can keep that fire blazing as long as you keep throwing thought logs on that fire. The problem is that these are not the natural emotions from the event. The fire does not burn out, because it is being fuelled by different thoughts like self-hatred, blaming people who weren’t responsible for that particular event, thinking that all people are bad or untrustworthy, and so on.

Introducing your primary trauma

During the course preparation section, you listed some of your most troubling traumatic experiences. Looking back at this list we would like you to note which is the event you are most bothered by currently.

“Which event do you have the most nightmares about or most often pops into your head when you least expect it?”

For this OTR course, we will look at this one event, it is currently your primary trauma. By looking at peoples primary trauma we find that it can release other traumas most effectively. If we open up too much of your trauma the effect can be frightening and stop you from completing this OTR cycle. By staying focused on this one event you will safely learn and practise the skills to change your response to this event. You can then use these skills for other traumas that are bothering you, or complete another cycle of OTR if you need to.

TASK 1.2

- Write a short description of your primary trauma.

- Concentrate on the ‘facts’ of what happened. At this stage, it is best not to talk about feelings and thoughts.

- A simple outline of 200 hundred words or three minutes talking is enough.

- If you become distracted or overwhelmed by the feelings and thoughts use a simple grounding exercise before carrying on. Reach out to your support network if you need to.

Review of Session 1

“People CAN change their minds”

This sounds like a bold statement, and although it sometimes takes persistence, it is true. Changing your mind is a skill that the OTR course will teach you. You don’t need to know what changing your mind feels like or have any idea how to do it right now. Step by step you will be guided to learn the skills that will help you change your mind. You may well be wondering “Why would would I want to change my mind?”. If it was working for you, would you be here asking for this help?

As you have learnt, avoidance of feelings and triggers are the core of PTSD symptoms, these behaviours are not working for you. Through OPT, a step at a time, you will learn the skills to know the difference between a fact and a thought. You will practice and understand deciding how you feel when you think those thoughts. The tasks in OPT will help you to put your keep track of your thoughts, reexamine the facts about your trauma and chose to think about it differently.

The last task of Session 1 is to start looking at why you think your index trauma happened. Well done for getting to this point. Once you have completed this task take some time to ground yourself and recognize that you have started your recovery journey. Before the next session taker some time to review the sections on Stuck Points and PTSD Symptoms from this session.

TASK 1.3

- Write one page on why you think your index event occurred. Once written, put the page away safely until your next session, don’t need to look at it before then.

- You are not being asked to write specific details about this event. Write about what you have been thinking about the cause and effects of this event.

- ADD STUFF TO WRITE ABOUT CAUSES

- Some of the things you may want to write about are the effects this traumatic event has had on your beliefs about yourself, others, and the world in the following areas: safety, trust, power/control, esteem, and intimacy.

- There is no right or wrong way to write this. Things that may help are; using I statements (I feel, I think, I believe, If I had, If I hadn’t); temporarily putting aside the PTSD symptom of avoidance; MORE

- If you become distracted or overwhelmed by the feelings and thoughts use a simple grounding exercise before carrying on. Reach out to your support network if you need to.

Your next session is: